Usually on Design Disciplin, we ask the questions. This time, our guest is the interviewer.

Designer Anthony Hobday asked the questions, and I answered.

We spoke about the place of visual design in modern, technology-centered design education – UX and interaction design.

Anthony is a generalist product designer, particularly interested in interaction and visual design. He is an explorer in the world of design, through his many side projects, blog posts, books, and tweets.

You can find other interviews that Anthony has done with professional designers on his website.

What is your relationship to visual design?

Baytaş: Design is my purpose in life. I always wanted to be a designer. But when I was young, I didn’t know that "design" was the name of what I wanted to do.

As a child, I loved sci-fi movies. Movies like Back to the Future, with the stereotypical inventor/scientist. I was led to believe that it's scientists who have the job of inventing things. So I would say, “I want to be a scientist.”

Then I learned about engineering. My cousin got married, and her husband is an engineer. So in my early teens, I wanted to be an engineer.

Finally, when I was in high school, my parents bought our first home. With the new home, came new furniture. Some of this furniture was more interesting. It was more expensive. It received more care. I was instructed to be careful with it.

Even the shop where we bought these from was more interesting. Delightful place – I still remember the layout and the textures. (Later I learned that this was Koleksiyon, founded by Faruk Malhan, perhaps the leading Turkish industrial designer of the time.)

I remember asking my mom, “Why is this stuff more important?” She replied: “It’s design.”

From that point on, I knew that what I wanted to do was called "design." And I knew that I was more interested in designing how things look and feel, rather than the unseen parts of them.

At the same time, I had another obsession: computers. I played a lot of computer games. I loved strategy games like Starcraft and Command & Conquer, with a lot of UI (at least, compared to action games).

One day, I realized, there must be someone who makes this stuff. And since they are selling these games for money, this must be a job you can do for a living! I remember being so excited about this idea, I literally picked up the phone and called my best friend to tell him, “bro, I literally found what I will do for a living when I grow up – I will be a UI designer!”

(I’m honestly quite impressed with my teenage self in this story, because this was the early 2000s. I did not have internet. UI design as a profession did not exist in Turkey, where I was growing up. Twitter did not exist. Facebook was just born.)

In high school, I learned web design, HTML, Photoshop, etc. One of my design memories from the time was winning the school election, to be the vice president of the student council. My victory came after a set of posters we made in Word and Photoshop on the school computers, with celebrities and Star Wars characters endorsing me.

So I loved design. But it felt too effortless. I didn’t find it challenging. And there weren’t many attractive work opportunities for designers in Turkey at the time. So, after all of this, I went to school for engineering.

During school I did a lot of web design as a side job. Went to work for a startup afterwards, and even though it wasn’t the job I was hired for, I ended up designing internal GUI tools for warehouse operations. (When UIs were still called GUIs...)

Less than a year later, my university where I had studied engineering started a new graduate program for interaction design. Almost immediately I signed up and quit my job. (It was a funded research fellowship where my salary was only slightly less than the startup job.)

Fast forward 10 years: I have a PhD in interaction design, 30 publications as a design scholar, raised and managed $4M of funding for design research, etc.

Now, the reason this story is interesting is because, up until this point, I never took visual design very seriously. I signed up for web design courses, master’s and PhD, design research projects – a lot of work that has to do with technology, innovation, "design thinking"… I expected that I would be taught or directed towards visual design in these programs. I expected that it would come up. But in the worlds of tech and higher education, as I experienced them, visual design was always second-class citizen. The first thing I was taught in the design master’s was “design is not about how it looks.”

Sure, design is not entirely about how things look. But the way things look is still a crucial part of design. And the topic was cast aside!

When I learned web design, I was taught HTML tags, and If statements in JS. In fact, CSS – which is the markup language for visual design on the web – was the last topic on the agenda, and it wasn’t even covered in full, because we ran out of time.

So how does one learn visual design, if one wants to work in tech, on the digital medium? I didn’t know. Perhaps it didn’t exist at that time and place. Art school existed of course, but I could barely hold a pen. I didn’t belong there.

I completed a PhD in design. I moved to Sweden, which is supposed to be a “design country,” to do design research. But I realized, even at the interaction design department of my Swedish university, almost no one interested in visual design! (At least, none of the faculty – I learned plenty from our students.)

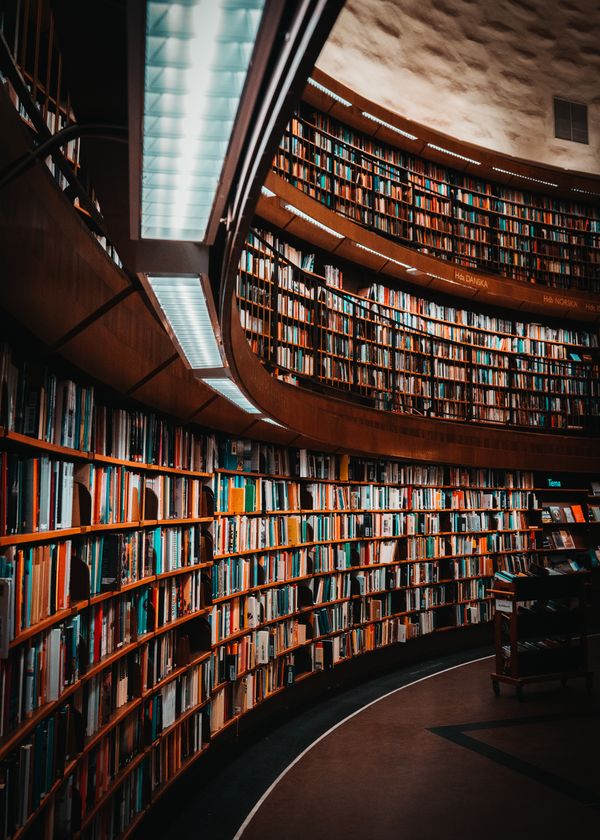

I took matters into my own hands and hit the books.

Now, I have a growing collection of graphic design books: Josef Müller-Brockmann, Armin Hoffman, Jost Hochuli, Kimberly Elam, Emil Ruder, Ellen Lupton, Timothy Samara, Michael Bierut, Adrien Shaughnessy... I have the books on Virgil Abloh and Hiroshi Fujiwara. I have books from publishers like Unit Editions and Lars Müller. I’m still buying them up all the time.

It’s only after finding the knowledge in these books, that I can call myself a designer, and say that I know visual design. I’m astounded that this knowledge was almost completely ignored in my design education on UX, UI, design thinking, service design, etc.

I only became aware of this knowledge when I was teaching design at the university. I was visiting design studios to organize guest lectures from professional designers (which is how Design Disciplin got started). Many of these designers came from traditional graphic design and art school backgrounds, and they had hundreds of these books in their studios.

The first time I learned about “Swiss Design," I already had a PhD in design! After two decades of chasing visual design knowledge, it’s only now that I feel like I have found it.

This brings me to the actual answer to the question: What is my relationship to visual design today?

After two decades of study and work – of which one decade is full-on academic research in design, and two years are deep studies of visual design from these books – and more projects than I cared to count in UX, UI, physical product design, etc., now I am able to confidently call myself a "design expert."

My purpose today is to use and teach this expertise. I turned my focus back to my professional practice, after a decade in academia. I founded Design Disciplin, an online institution publishing articles, videos, and a podcast informed by multi-disciplinary design research. I also teach at professional schools and train teams at companies.

What do you see from designers and university faculty that suggests treat visual design as a second-class citizen?

B: First of all, I should not be unfair to the faculty at my department. I’m not privy to all of their intentions, and there’s plenty of things going on at the university that I haven’t participated in. Maybe some of them share my faith in visual design.

To your question, it’s more what I don’t see. Here are some of the topics prescribed in graduate-level design education:

- "Process” e.g. design sprints, Design Thinking, double diamond...

- User studies, surveys, interviews...

- Workshopping, brainstorming, affinity diagramming...

- Quantitative research, e.g. particular "instruments" like questionnaires, statistics, eye tracking...

- Social-scientific methods: ethnography, anthropology, sociology...

- Theory, philosophy, ethics...

- The history of human-computer interaction

- Technical requirements specification

For a concrete example, you can see the contents of the Interaction Design book by Rogers et al., which is a common textbook on the subject. You can see the headlines of the courses and literature offered by the Interaction Design Foundation.

Compare this with design education outside of the academic establishment. For example, look at Shift Nudge, a new comprehensive UI design course for tech industry. The topics are: typography, layout, color, imagery...

Or compare to topics in undergraduate education in graphic design, architecture, industrial design...

Graduate level design education as I have experienced it does not produce designers. It produces design critics.

Topics like qualitative and quantitative research, process and theory, ideation workshopping, etc. are not unimportant. But designers need visual design skills, in order to do justice to their knowledge in such topics.

A designer educated fully in theory and methods but not in visual design is like an expert programmer who is trying to write code with pen and paper. Or an expert surgeon without hands.

But in academia, hands-on skills are not valued. It’s not part of the system. The main currencies in this system are scholarly writing and social connections. A designer who has produced hundreds of artifacts, won awards, etc. may not even be considered for an academic job. But theorists who have never designed anything become highly distinguished professors.

On the systemic level, faculty are not rewarded for doing design work. Instead they are expected to spend all of their time on talking about design. Doing design is seen as a distraction.

Why do you think visual design is treated this way?

B: There is a lot about visual design which is subjective. Matters of opinion and taste.

Matters of opinion and taste are usually avoided in the university departments that I’ve had the chance to experience. The desire is to be objective and scientific, as much as possible.

It feels to me like the goal of much of this education is to produce designers who completely remove their opinions and taste from the design process. They are to act merely as conduits between the “users” and the business. Anything that cannot be processed scientifically/systematically towards a high degree of objectivity is not the domain of this education and the designers it trains.

In contrast, I have visited schools of art, architecture, industrial design, where I have seen a “studio culture" with critique sessions, etc. The teaching and learning relied on a lot of subjectivity. And it was always the case that the work that these students were doing was more visually compelling and “finished” aesthetically, compared to the systems that I came up from.

I’d go as far as to say that today there are two different approaches in the design profession. I find it very confusing that they are both called “design."

One is an approach where the designer is expected to have a style, a personal touch. This is more common in graphic design and industrial design. If you view the portfolios of leading graphic design studios, you see some degree of stylistic cohesion. If you look at portfolios of industrial designers, you'll see consistent preferences towards certain materials and forms.

The second approach is where the "designer" is a conduit between different stakeholders. This is common in UX design, service design, etc. Many of these designers do not even produce any visual work that is seen by the public. They might produce wireframes, personas, internal documents, conduct workshops, etc. I personally think we would be better off calling these people “facilitators” or "strategists" or “advocates,” etc.

Both of these kinds of work are valuable and necessary. But the academic design education I experienced was almost 100% about the second. I wish this is communicated more honestly and explicitly to students they are trying to attract. Instead of "design," I wish I could rebrand these places to something like "department of strategic facilitation" or "collective decision-making studies."

If we return to the question of why...

- It seems that in today’s academic environment, subjectivity is generally discouraged. And visual design necessarily involves a lot of subjectivity.

- It may be that there’s a correlation between artistic/visual focus and teaching/people-focus. Some people are drawn to doing hands-on, tactical, visual work. They become practitioners. Some are drawn to people, teaching, mentoring. These people thrive as teachers. And universities appreciate and promote people-people, rather than tactical-people.

- Corporate environments especially, and perhaps business generally, appreciates and promotes facilitators rather than tacticians. It’s simply more profitable to be the second kind of designer. There are clear career paths to advance in management, while consistent advancement as a tactician or individual contributor is more of a rare find.

Thus, today we have entire branches of the design profession where visual design is a second-class citizen, if a citizen at all.

Is there a way to encourage that "studio culture" approach in designers at scale? If designers want to teach themselves, for example?

B: I found a lot of great visual design knowledge in books. Physical books are a great investment for designers.

First of all, books are packaged as a whole “curriculum." Just looking at the table of contents in a well-considered book, we can get a good overview of the discipline. And then they are “flippable.” We can pick them up and quickly go through the pages for inspiration while on the job.

Many great design books are unavailable in digital formats, or the reading experience is not as pleasing. Physical books are still the best format for a lot of great visual design knowledge.

There’s also a lot of great design content on social media. Simply browsing and following designers on Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, one finds many masterclasses. A lot of designers also share their process, not just the outcome. Social media is actually a great place to learn design. In fact I have a whole Instagram account that I sometimes switch to, where I only follow design studios etc., for inspiration.

These days, there are also online communities, many on Discord. These are great places to get feedback from other designers. I host the Design Disciplin community on Discord, which has a multi-disciplinary focus. Other popular ones are Design Buddies and DesignCourse.

Is there a particular book you’d recommend if someone wants to learn about visual design?

B: I wrote about this recently. We published a post about the best modern books on layouts and grid systems.

In addition to this, I like Geometry of Design by Kimberly Elam, Michael Bierut’s How To, A Smile in the Mind...

I love Virgil Abloh’s books – the one on his Nike collab, and the other on his artworks. I like Armin Hofmann’s Graphic Design Manual, which goes deep into the very basics.

Is there anything we haven’t covered that you think is important about visual design?

B: There’s one thing that experienced designers know, which doesn’t always occur to beginners, but it’s very high-leverage. And that is to look outside of your own discipline to find ideas, learnings, tactics.

Let’s take UI design. You can look at industrial product design, photography, filmmaking, games, animation, etc. to find great ideas, rather than studying UI design specifically, and looking for ideas in the work of other UI designers.

There is great value in studying...

- The absolute basics, the first principles – geometry, math, biology, human senses and perception, even philosophy...

- Image-making and object-making disciplines outside of one’s own, even outside of what we consider “creative” disciplines (for example engineers, physicists, mathematicians have developed incredible diagramming techniques)

Obviously it’s hard to be productive if you spend all your time studying a great variety of complex subjects. But occasionally taking a pause, to deliberately go into another discipline, in order to get ideas, will certainly improve your work as a visual designer.

I’ll finish with some concrete examples of this. Some "homework" if you will, for UI designers:

- Read one of Michael Freeman’s books on photography

- Watch a YouTube video on the techniques of Renaissance artists

- Join a pottery workshop

- Pay attention to the costume designs in the next time you watch a sci-fi movie

- Visit a magazine stand and observe the standards in cover designs, as well as how and why some of them stand out

You might say, this negates what I argued earlier: to be centered on our visual design skills. But I'm not suggesting to take up these extracurricular activities at the expense of our home discipline. Quite the opposite: the "homework" is to acquire lessons to inform our visual designs.

Visual design is how we take our inspirations, and the work that we do in the strategic dimension, and actually materialize it, bring it into the world. Without visual design, are we even designers?