Supported by:

Daylight Computer: the healthiest computer

Baked Graphics: amazing 3D video mockups

Framer: the best website builder for designers

ProtoPie: the best hi-fidelity interface prototyping tool

Design Thinking is a religion with two core beliefs:

Design can solve all problems. It doesn't matter what your problem is – sales, education, science, global pandemic... Design will give you a solution.

Design can be done by all people. Skills, training, experience, talent – none of it matters. You just have to believe in Design Thinking, and you can become a designer today.

Of course, these are not true. But they are dangerously close to the truth of how Design Thinking is perceived.

In reality, Design Thinking is an incredibly successful information product and marketing campaign. It's also a brilliant example of how, over the course of half a century, philosophical ideas from academia can be transformed in the right hands into an industry worth millions.

The story of Design Thinking begins as a philosophical research topic, which supplied the ingredients to the original recipe for "Designed in California" before it became a packaged product and a massively popular belief system.

The Philosophy of Design Thinking

What we call Design Thinking today was actually born as a question: How is it that designers think? How is design done?

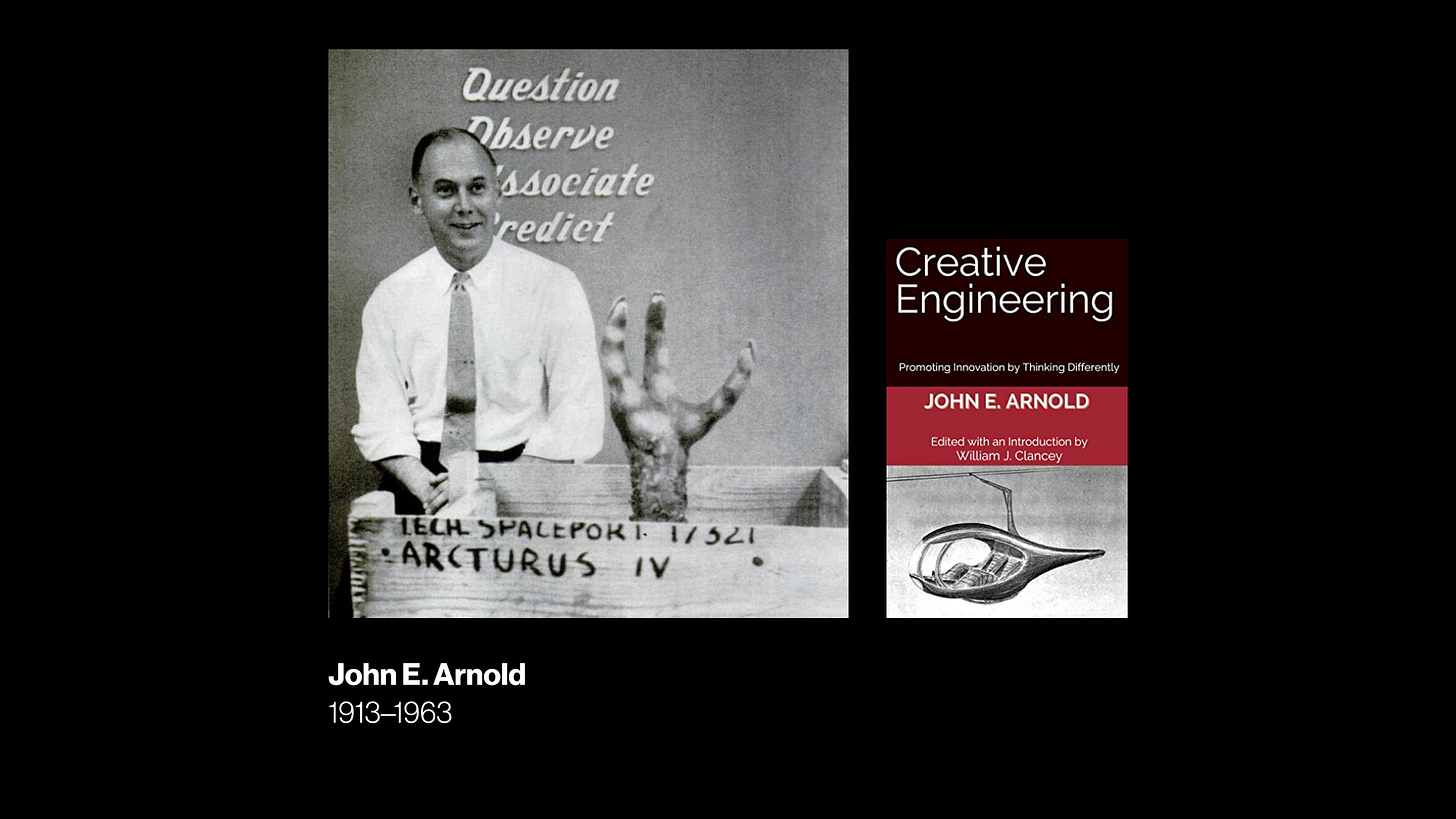

One of the first people to write about "design thinking" was John E. Arnold, a professor of engineering at MIT and then at Stanford, who sought a science of creativity to advance engineering and business innovation. Arnold is a pioneer – in the 1950s, he laid the foundations for how we think about design and innovation today.

In 1963, Arnold passed away at only 50 years old, but the topic of "design thinking" attracted many of scholars like Bruce Archer, Herbert Simon, Horst Rittel, Nigel Cross, and Donald Schön in the following decades. "Design thinking" during this period is practically synonymous with design philosophy or "research into design."

Put simply, design thinking research has two interrelated aims: To "reverse-engineer" creativity, and to promote institutions that teach and use it. It argues that there are things like "designerly ways of knowing" and particular methods of doing things; which are distinct from (and as valuable as) things like scientific knowledge and engineering methods. It wishes to substantiate design as a profession. It makes perfect sense: these people are scholars of design, and they want to have schools of design where they will have jobs.

Jokes aside, here's a true story: The last time I was filling out a form that asked for my occupation, neither "researcher" nor "designer" were among the options. I had to say that I'm an engineer, since that's what I went to school for.

The Process of Design Thinking

Now, obviously, the question is: What are these "designerly ways?"

"Design thinking" was about answering this question. The job was to study and analyze the work of designers, and to put that into words, to educate more designers – and to educate everyone else to understand them.

Design thinking research came up concepts, frameworks, models... – all very sophisticated descriptions of design work. However, it's not entirely plausible for this research to give us a prescriptive method or process for how we ought to do design. A process you can actually use in practice has to come from, well, practice.

The definitive process of Design Thinking comes from a company called IDEO.

IDEO is a design company originating from California. They design a lot of things, but they don't manufacture and sell any of them. IDEO is a design consultancy that creates products for other companies.

IDEO is the original gangster of "Designed in California" – they created Apple's first mouse.

Today IDEO is arguably the most successful design company in the world. They have been around for more than 30 years (or 40 years, depending on how you count), and this kind of continuity itself is impressive for a design consultancy. And one of the secrets to IDEO's success is how they radically expanded the scope of what "design" means – and thereby, what kinds of projects they take on.

In the 1970s, IDEO started as a couple of friends working on small-scale mechanical engineering and industrial design projects. Today, IDEO is a global company with close to a thousand employees. There's no limit to what they work on: branding, marketing, electronics, food, healthcare, management consulting, software, education...

So how do you turn a little workshop into a worldwide company?

You do it by defining a method, a process your people can apply in all of your projects. This process must have its roots in the design and engineering practice at the company's origin. This process must be framed and described in a way that applies to all of the new business that you're interested in. This process is Design Thinking.

And this Design Thinking is the same design thinking that scholars have been contemplating since the 1950s; because this is where the founder of IDEO, David Kelley, got his education.

David Kelley graduated in 1977 from Stanford's Joint Program in Design, a program that brought together the engineering and art schools – a program initiated by none other than John E. Arnold.

Arnold proposed ideas like human-centered design and multi-disciplinary design education in the late 1950s, but passed away before they could be implemented. Fortunately, his colleagues at Stanford continued the work and created the design program, where David Kelley went to school before he started IDEO.

Kelley's IDEO arranged the concepts and language of design thinking research into a practical process. They used it to plan and coordinate their projects, and to explain what they do to everyone else. IDEO was made in the image of Stanford and John E. Arnold.

But here's what's curious: For much of IDEO's history, if we look closely at the way they talk, it's hard to find any mention of "design thinking."

There's a famous episode of ABC's Nightline where they visit IDEO in 1999, going through the process of an entire project. This is around 20 minutes of IDEO staff explaining what they do. And nobody ever says "design thinking."

In 2001, David Kelley's brother Tom Kelley publishes The Art of Innovation – an entire book on IDEO's process. And the phrase "design thinking" is does not occur anywhere in it.

The productization of Design Thinking hasn't happened yet.

The Product: Design Thinking

Tom Kelley has published other books. 2005's The Ten Faces of Innovation does mention "design thinking," but only 3 times. Then, in 2013, he and David Kelley write another book together: Creative Confidence – with 50 references to "design thinking." Something has happened during the 2000s.

What has happened is that in 2000, IDEO appoints a new CEO: Tim Brown.

I'll admit that I'm very intrigued by Tim Brown. I think he is a genius – and not because of the clever ideas that he talks about. Tim Brown's genius lies in a very powerful secret that he keeps to himself.

Like David Kelley, Tim Brown has roots in academic thought on design thinking. In the 1980s he went to Northumbria University and the Royal College of Art – hotspots for design research and philosophy. It's probable that he was taught by scholars like like Bruce Archer and Christopher Frayling.

Tim Brown is like the apostle of Design Thinking – the driving force behind how Design Thinking is perceived as something we could (and should) apply in any business.

Brown's work as IDEO's CEO is dedicated to promoting design to businesspeople. Hours of footage on YouTube shows him talking about design and how great it is for business. He has literally written the book on Design Thinking, Change by Design (where the phrase occurs 158 times). The website designthinking.ideo.com – the definitive address for Design Thinking on the internet – used to be his personal blog until 2018.

Tim Brown seems like he's all about design. But he has a secret.

The secret is that Tim Brown is a genius of business strategy, branding, and marketing. And it shows in the way he productized IDEO and Design Thinking.

“Productization” is a word I learned recently from the work of Jack Butcher, who picked it up from Naval Ravikant.

Generally, any business sells two things: services and products. A pure service business has innate limits. Even if you are the best in the world, you spend a lot of time selling your work to people, and you spend a lot of time executing unique projects.

Productization is about extracting a product business from a service business. If you have a successful service business like IDEO; you can take the expertise and methodology that makes it successful, and create information products from it. Take your process, write it down, give it a name, and start selling your knowledge about how to do the work – as a product that earns while you sleep.

This is what Tim Brown's IDEO does, masterfully. It's amazing that he never talks about his strategy, but more or less every iota of his attention as IDEO's CEO was dedicated to developing the product: Design Thinking. He has written articles and books. He has launched websites that explain their methods. In 2015 he unveils an online school, IDEO U, to sell courses and certificates in Design Thinking.

This is the work of genius, because it has results which keep increasing and compounding. It creates what they call a flywheel effect1 – a positive feedback loop.

First, the books, courses, and workshops that teach Design Thinking are a source of revenue, largely divorced from person-hours. Then, as people learn and apply Design Thinking, successes and case studies accumulate to inspire demand for IDEO's original services, as well as the education products. Recruitment gets easier: newcomers are already trained in the company's process. And all of this massively increases the perceived value of IDEO's services: Today, for hundreds or thousands of dollars, you can find people everywhere to come and do your Design Thinking, or teach it to your team. But the original gangster who invented Design Thinking regularly works on million-dollar projects.

It's fascinating that Tim Brown never talks about it, but he is a true master of business. Even his book, Change by Design, is equally about innovation management and change management as it is about design – though neither "innovation management" nor "change management" occur anywhere in the book. Far from it: Brown will flaunt that he doesn't have an MBA – but only to give it away as he quotes Peter Drucker:

The most important thing in communication is to hear what isn't being said.

The Religion of Design Thinking

I joke around and say that Design Thinking is a religion2 with David Kelley as its prophet and Tim Brown as its apostle; because it has a massive following, with sects like IBM's Enterprise Design Thinking and Google's Design Sprints, and disciples who literally believe in its messages. It is also widely misinterpreted, I dare say, by most people – including those who do it, sell it, and teach it.

At its origin, design thinking is not about becoming a designer and doing what designers are supposed do. It's about studying and appreciating designers as experts in creativity, and collaborating with them.

The truth of IDEO's Design Thinking – if you read their books and take their courses – is far from a simple recipe that will make you a designer. It's a system of exercises, like lifting weights. If you talk to people at IDEO, you hear them talk about "design muscles" – to be developed and maintained over time.

Ironically, the truth of design thinking has very little to do with thinking. Doing is the truth of design.

Books, Links, and Resources

Build Once, Sell Twice: The Productization Playbook by Jack Butcher

Change by Design by Tim Brown

Creative Confidence by Tom Kelley and David Kelley

Creative Engineering by John E. Arnold

David Kelley: From Design to Design Thinking by Maria Camacho

Good to Great by Jim Collins

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari

Interview with David Kelley by Alex Pang

Religion for Atheists by Alain de Botton

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari

The Art of Innovation by Tom Kelley

The Ten Faces of Innovation by Tom Kelley

The Roots of IDEO's Design Thinking Process by Dexter Francis

The flywheel effect is a concept coined by the leadership scholar Jim Collins, who identifies it as a key characteristic of high-performing companies in his book Good to Great.

Inspiration for my "Design Thinking as religion" analogy came from two places: One is how Yuval Noah Harari uses the term in reference to value systems like liberalism and socialism in his bestselling books Sapiens and Homo Deus. The other was how Alain de Botton reveals how many aspects of religions are useful to modern life in Religion for Atheists.