On December 1, 2021, I gave a talk on Research through Design at a meetup organized by Got UX (IxDA Gothenburg Chapter), in collaboration with Design Disciplin and Recorded Future. The audience was mostly professional UX designers and researchers, and a few graduate students. This article has been adapted from the talk.

Abstract: Research through Design is a way of materializing knowledge and insights based on hands-on design work. It’s an exciting world where designers can do scientific research and get advanced degrees based on creative work. It’s also where many ideas in human-centered design, design thinking, lean, etc. originate and continue to be developed.

This is an "off-schedule" article, available on the website only. Upcoming episodes on our podcast and YouTube channel will cover Research through Design in depth – stay tuned.

You Are Here

Research through Design should be interesting for those of you who want to do design – to get hands-on, doing creative work – while doing scientific or academic research at the same time. This includes, but is not limited to, projects at masters or phd-level school. If you want to advance in the world of universities, and at the same time, do creative design work, this could be where you belong. But it's also relevant if you’re doing innovation work at a company, or “product” functions – design, product management, UX research…

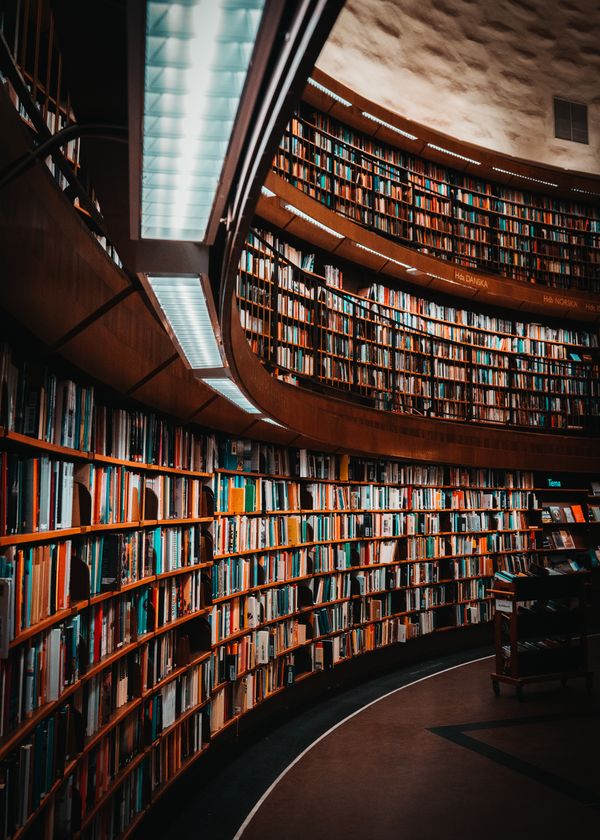

Most of the resources you'll need to do Research through Design will be in academic literature. Before you dive into it, this crash course will hopefully give you a map of what to expect – think of this as a map you find at the entrance of a park. To draw this map, I'll make comments on three resources which are canonical for Research through Design. These are what pretty much everyone refers to, when they are writing up their projects:

- Christopher Frayling's commentary on Research in Art and Design from 1993

- Research through Design as a Method for Interaction Design Research in HCI – an article by John Zimmerman and colleagues, from 2007

- The book Design Research through Practice* by Ilpo Koskinen and colleagues, from 2011

These are academic texts, so they are not always highly legible and to-the-point. I will try to show what some their actual points are – at least how I see them, and how I find them helpful.

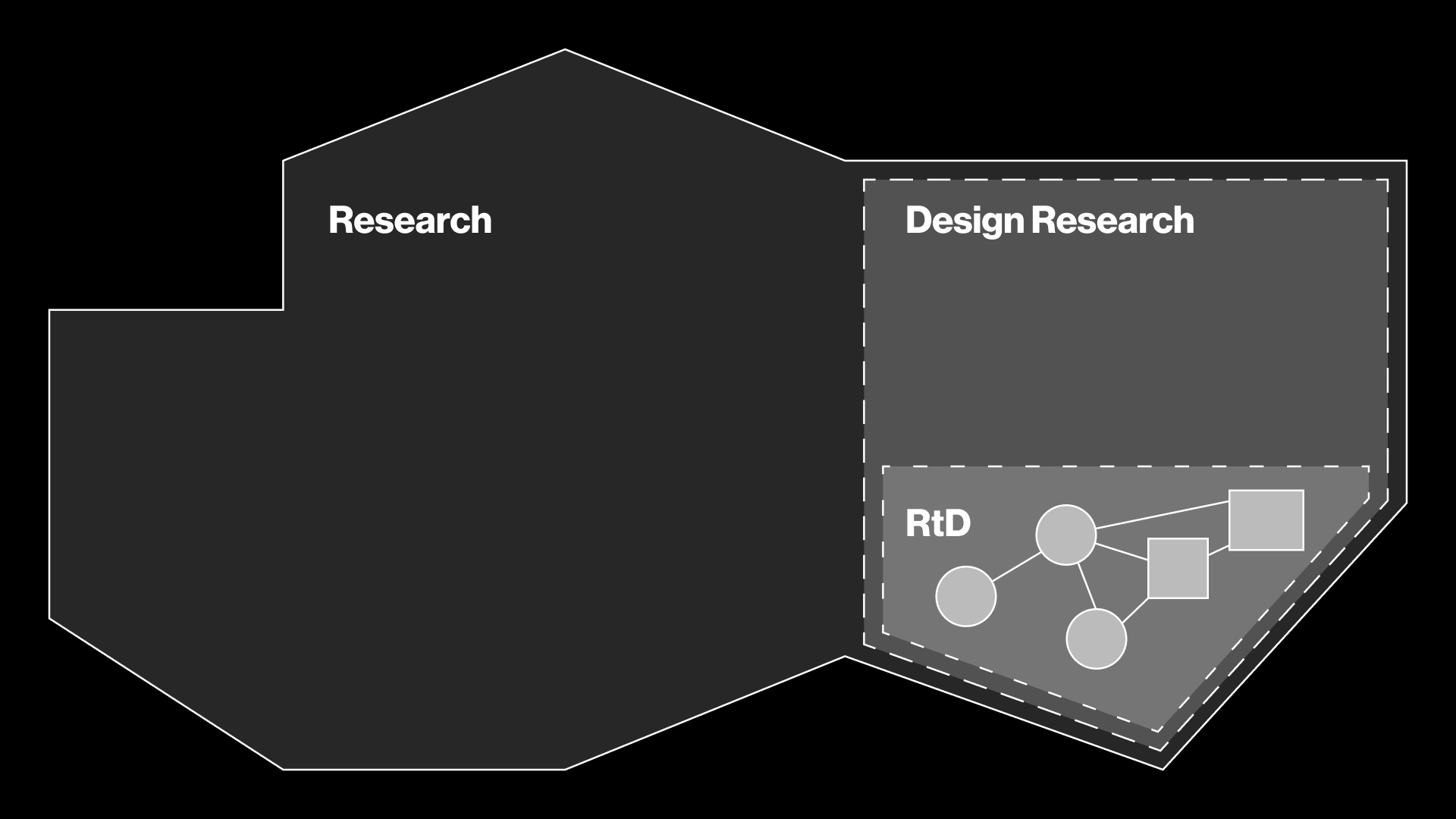

With Research through Design, the main category we are in – the “world” we are inhabiting – is the world of design research. And this can actually mean a few different things. Design research could involve, for example, interviewing users or customers. It could involve prototyping and engineering. It could involve writing papers, for academic purposes. Meanwhile, the skills and character of people who are good at these things can be different. Someone who’s good at going out and interviewing people might be a different kind of person, compared to the one who’s good at fabricating prototypes. And what if you want to write a book about the history of design, or to make a documentary? That could be design research too, but it’s a different mindset from doing product interviews, prototypes, or strategy.

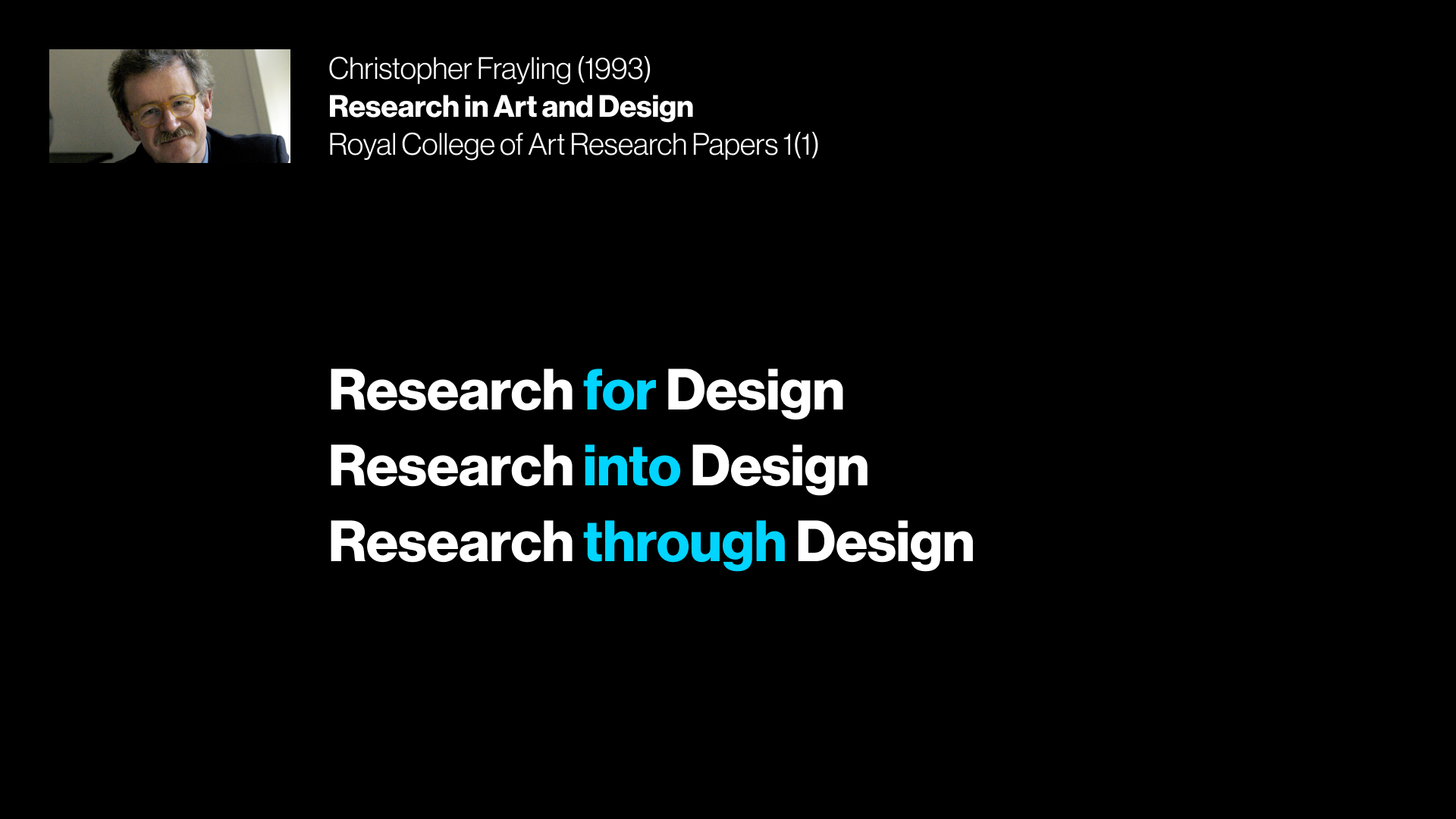

To get around this problem, I like to refer to a classification laid out by Christopher Frayling in the early 90s.

Christopher Frayling is a professor at the Royal College of Art. He’s actually a knight – Sir Christopher Frayling – in recognition of his services to art and design education. So he’s a big deal. And in 1993, he published this idea about how to classify design research, saying that there are three things which "design research" could mean.

The first is when you’re doing research in order to do design. Finding out about your users, your materials, market research... He calls this Research for Design.

The second is when you’re doing research about design, which he calls Research into Design. Think about, anthropology of a design studio, or history of Swedish product design…

What's interesting to me is that, when you’re doing one of those two things, you are probably not doing design in the traditional sense – graphics, modeling... But what if you want to spend your time getting hands on? What if you want to do, for example, a master’s thesis in which you craft a product? In that case, you need the third category, which is Research through Design.

There is already an episode of Design Disciplin about all of that, so I won’t repeat the whole story. Instead, I want you to think about why Frayling thought it’s necessary to propose this idea. Why did he make this categorization in the first place? Keep that question in mind. And consider this…

research vs. Research

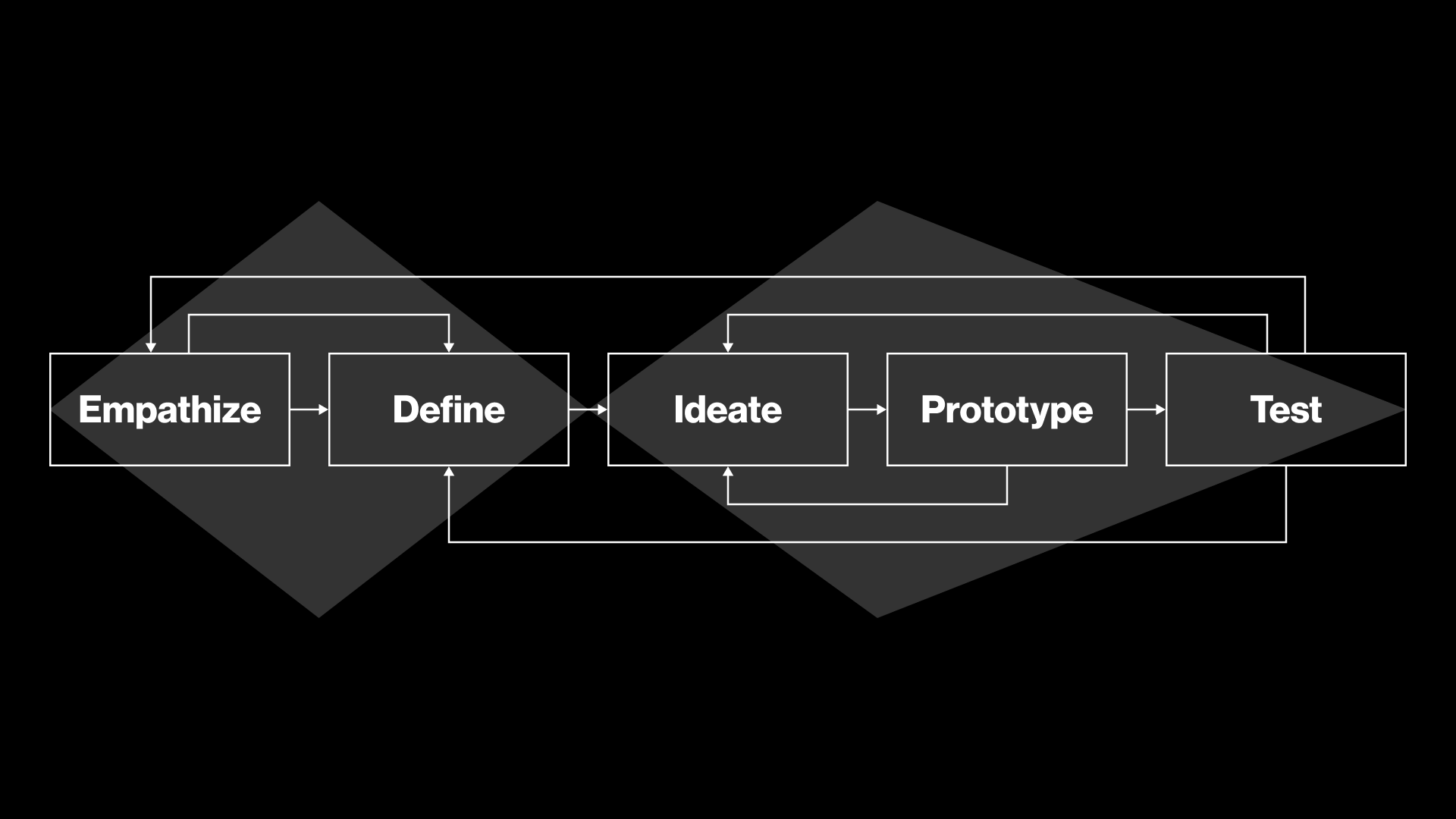

Think about the Design Thinking process, going through phases like Empathize, Ideate, Prototype... This is like a recipe you might follow, if you want to create products for a particular need.

Design Thinking is not a scientific research method, even though it actually involves a lot of research. Empathize – this could be like anthropology or psychology research. Testing is like experiments, user studies with your designs…

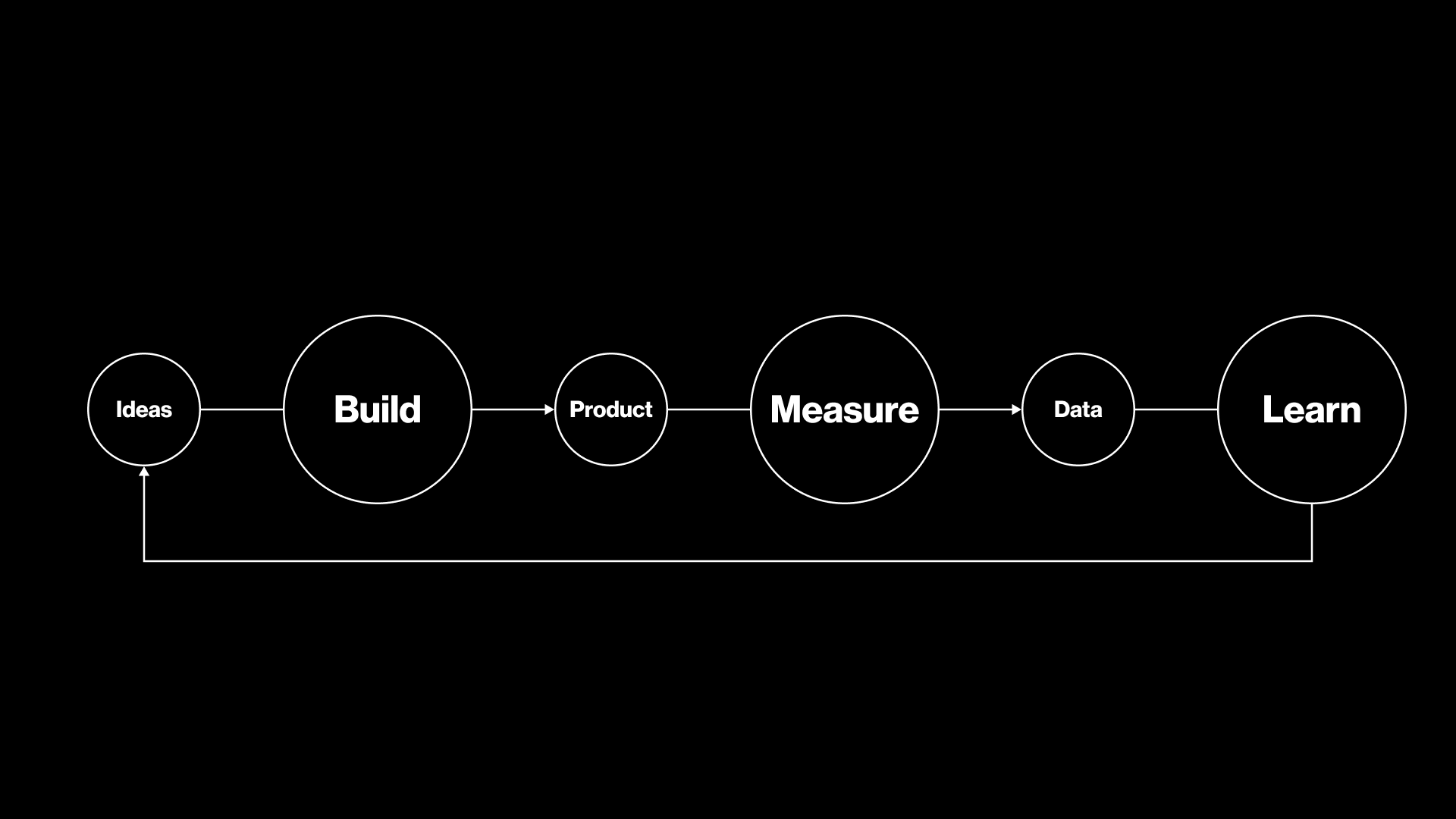

Another process to consider is from Lean Startup* – the Build, Measure, Learn feedback loop.

Again it says, learn and get ideas, get data... That’s also research. But this whole thing is not supposed to be a research method. The goal here is to create products, not to do science!

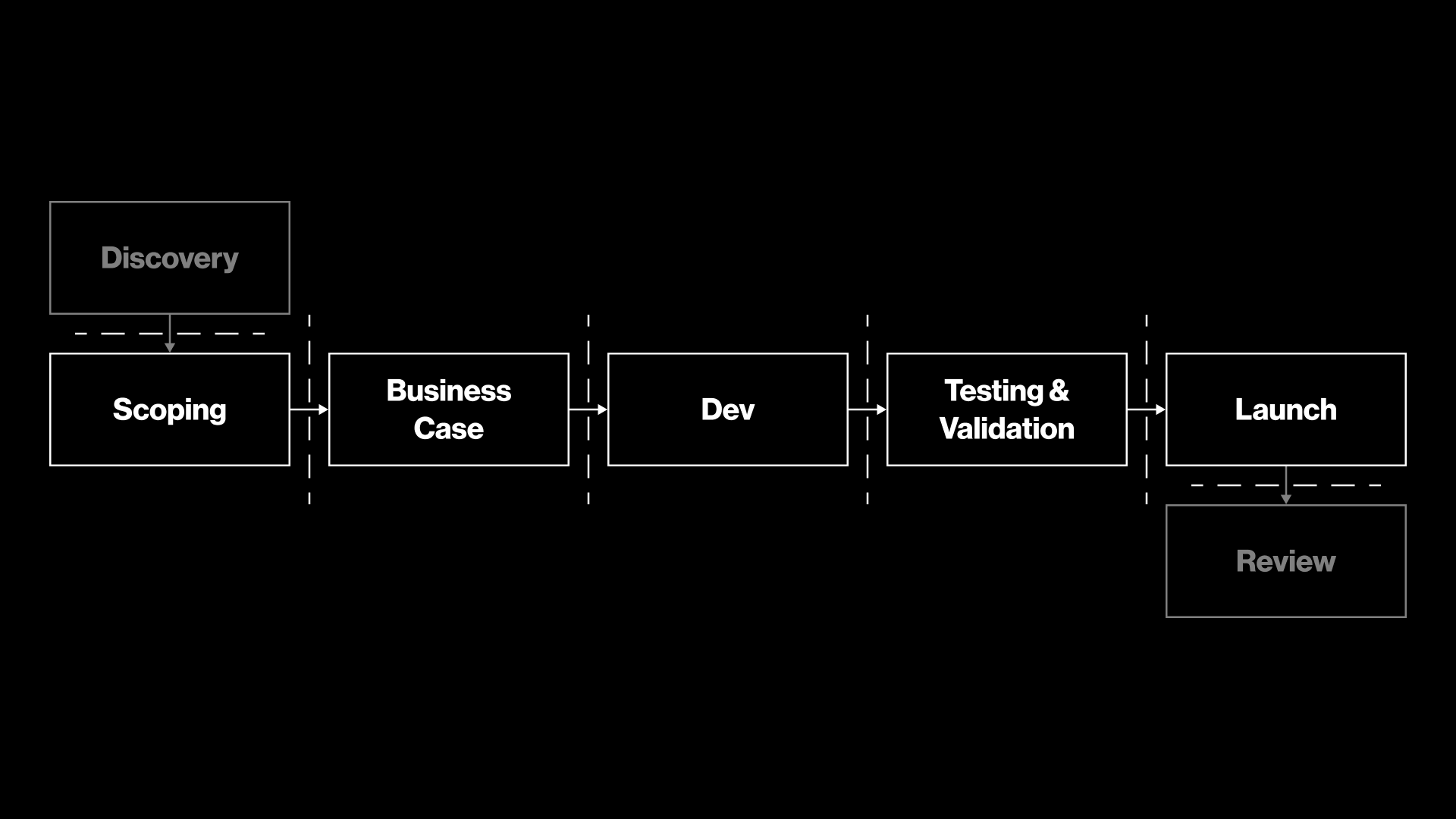

Finally, consider the Stage-Gate model – this is a little esoteric, but it's from the world of innovation management or project management. Discovery, scoping, validation, review – all based on research, really.

These are all from the business world. These are business processes for invention, innovation – creating new products. These were not intended to be research methods in the scientific or academic sense.

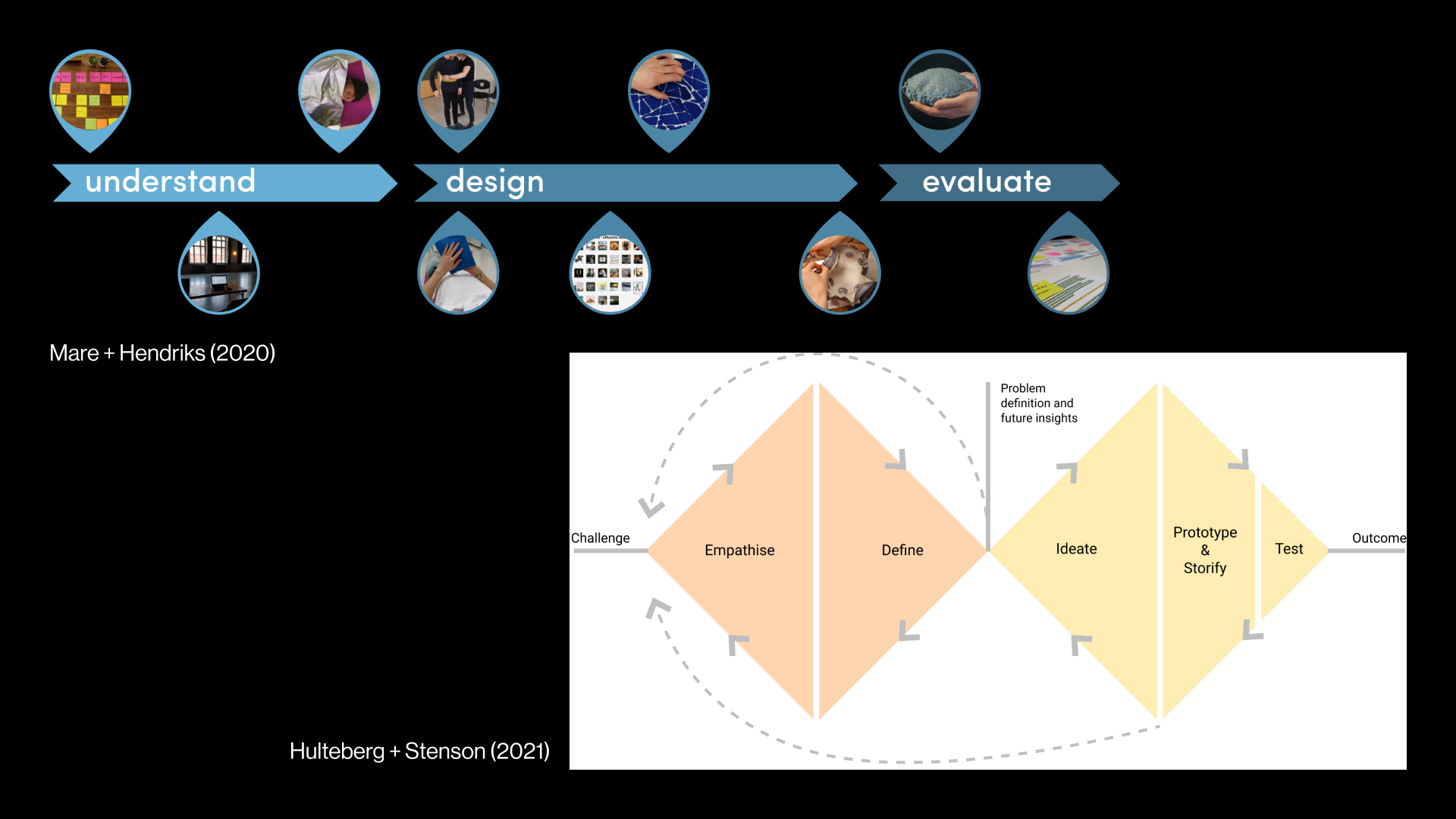

Despite this, our graduate students at the university have been using very similar approaches when they do design research: "Understand, design, evaluate..." "Empathize, define, ideate..."

This is their actual research methodology. They are not doing research into design – they are not going to a company to do an ethnography of how people use this process. The meat of their academic research is based on a process intended to create products. And this is really standard nowadays. This is the method people use in the majority of grad school projects that I see in interaction design, product design, human-computer interaction…

Here's the question: When did this become acceptable? Since when are you able to run a product design process or innovation management process, claiming that this is academic research, and it counts as a scientific research method? Since when are you able to have this accepted by your committee or your reviewers?

Or let’s consider another question: Why would it not be acceptable to do that? We just said that there is research in all of these things: the Design Thinking, the Lean Startup... But what is different between that research, and academic or scientific research?

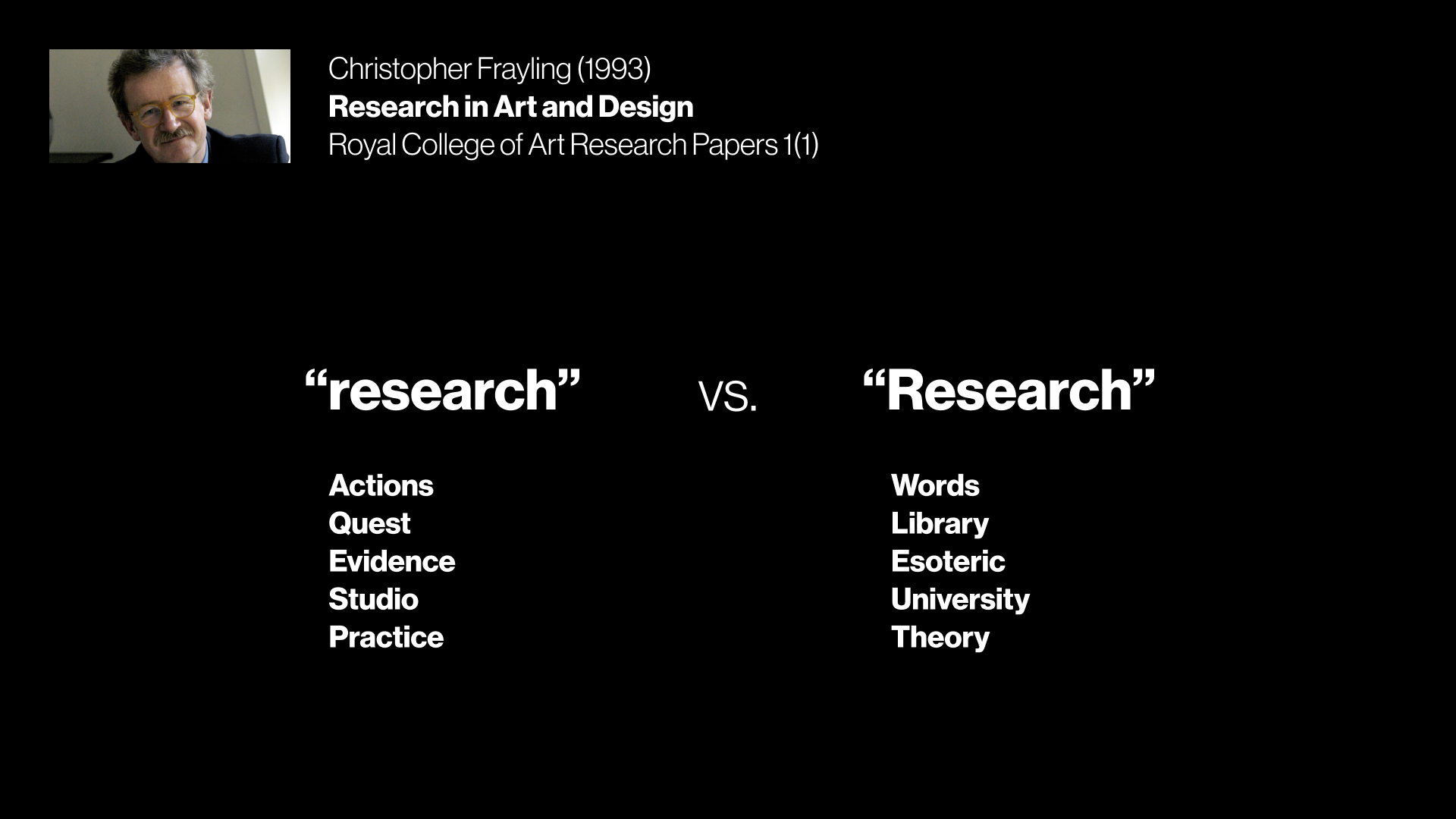

If we go back to Frayling, in addition to the three kinds of design research, he makes another distinction: he talks about “research with a little r” and “Research with a capital R.”

He points out that we indeed do research while we are doing design. But the character of this research is different from what he calls the capital-R Research – Research as a profession. This is the Research that is accepted in academic communities, the Research we find in scientific journals. It's Research as an object: it’s written down, as a document. It’s sophisticated and theoretical, it’s not really for everyday people – it’s for people with PhDs. Frayling actually calls this “esoteric.”

The research we do when we design is different. It’s research as an action. Frayling calls it a “personal quest” that artists or designers embark on. It’s hands on. It’s practical. You don’t need to write it down – you go and find out what you need, and you design, based on that.

The problem here is that this research does not qualify as academic or scientific. Without the Research with the capital R – without it writing down in scientific publications – you can’t have professors and degrees at the university. You can’t get research funding. You can’t start a university department and a grad school in design. All of that depends on Research with a capital R.

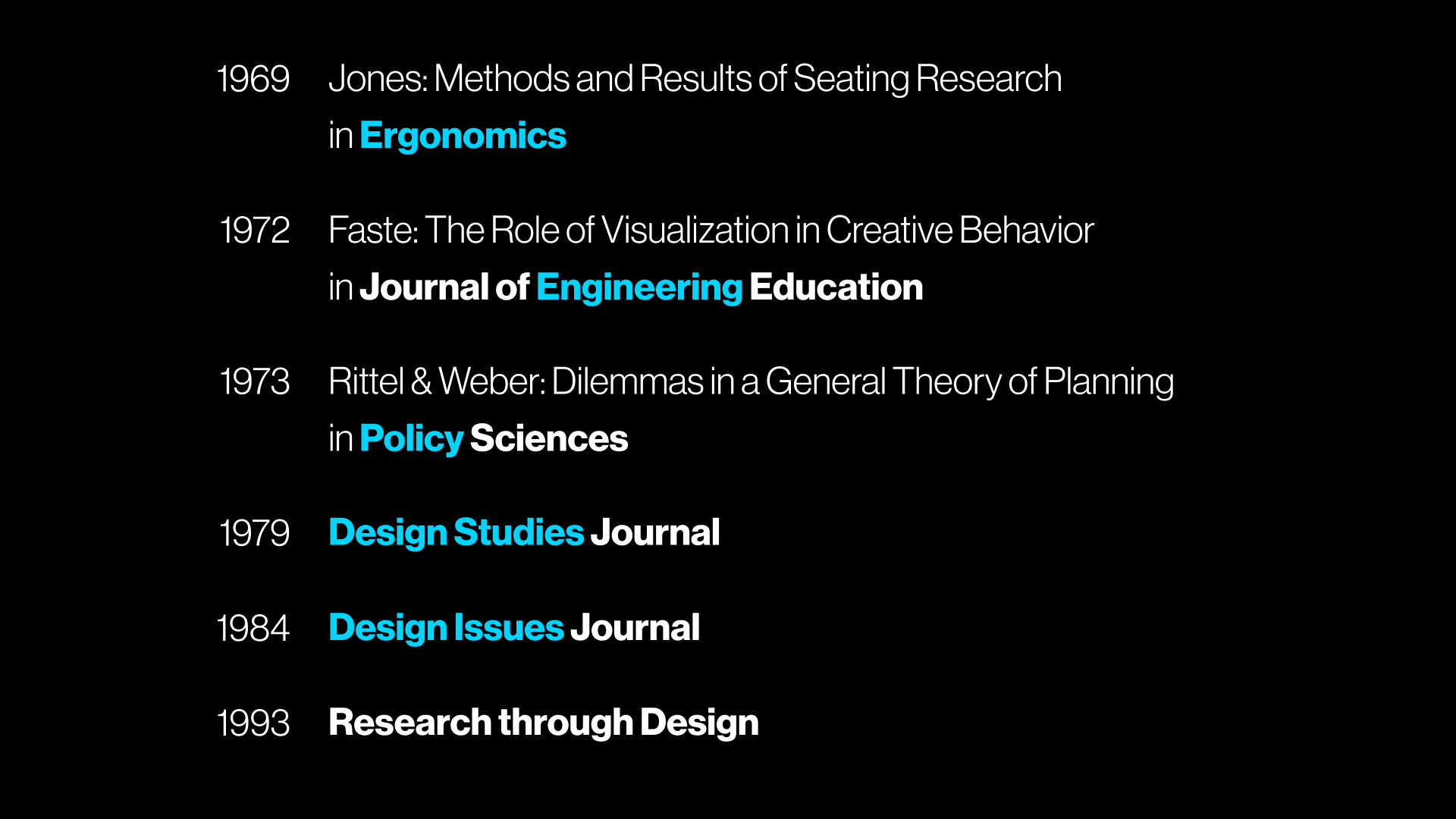

We have these things today. I have a PhD in design, and I supervise graduate degrees in design. But historically, if we go back 50 years ago, these things didn’t really exist. Design researchers, back in the day, did not have their own journals and conferences where they could publish their work. They published in journals about ergonomics, engineering, policy, math, education… The first journal for design research, Design Studies, was started in the late 70s – and if you look inside, actually, it’s a lot of research into design. It’s a lot of philosophy. It’s not double diamond, empathize, define, evaluate…

The “invention” of Research through Design, in the 90s, is the turning point for this. Now we have the foundation for being able to actually do design as a research project. Before this, if you did your double diamond, prototyping things for your paper or thesis, the response from your professors would probably have been: “What are you doing? That’s not a research!” If you said you’re doing design research, what they expect would likely have been to research into design.

True story: When I did my PhD, I failed my qualifying exam because of this! My research method was supposed to be based on Lean Startup.* I remember one of the professors on my committee asking, “Where’s your hypothesis? What’s your research method?” I had to retake the exam – because I hadn't framed and explained my method properly, based on this literature!

But now, thanks to Frayling's wonderful "invention," you have a legitimate response: “I’m doing Research through Design! Here, this is the paper to explain what that is, written by the most esteemed Sir Prof. Frayling!” Now it’s a legitimate research methodology.

Frayling has now set the stage for design and research to be integrated – for “Research with a capital R” to be produced from design. Now we can talk about the play we will perform on this stage. In other words: Frayling has now given us the land, the territory, where we can build. Now we must build the roads, buildings, and plumbing.

Now we know the history of how we were given this land. Next, we "zoom in" and look at the “buildings” – Research through Design projects.

What's good?

To understand Research through Design projects, and do our own, we need to ask two questions.

First of all, why are we doing this? What is the purpose of our project? Specifically, what kinds of research questions can we address using Research through Design? We might know, as designer/researchers, that this is the land where we want to live – this is the country where we belong. But as you know – especially those of you, like myself, who have been unlucky enough to not be born American or European – you can’t just show up in any country and settle down. You need to have a reason to be there.

You also need to know how you are going to do this research, before you embark on the project. What methods will you use? What kinds of criteria or benchmarks will tell you that you're on the right track?

Historically, in the literature, I’ve seen these questions answered in reverse: first the criteria, and then the methods. We can then get to the “why,” after talking about those.

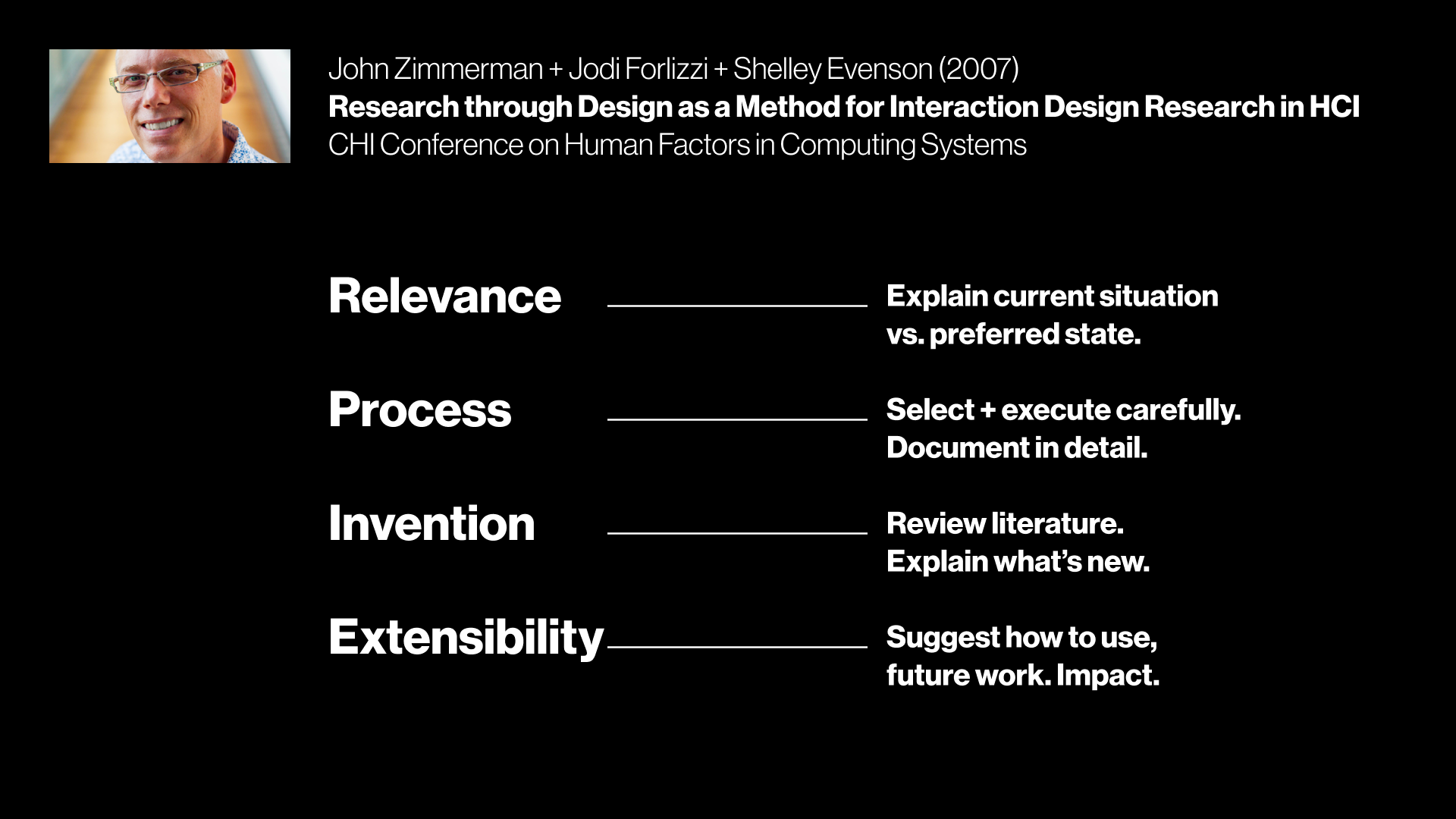

Let's talk about what counts. What is “good” Research through Design? John Zimmerman and colleagues from Carnegie Mellon University have written about this in 2007.

Side note: The Zimmerman paper, as well as Frayling, have been cited around 2,000 times. This means, if you want to read the entire literature on Research through Design, that’s approximately 2,000 papers.

Zimmerman and colleagues have interviewed design leaders at companies, as well as academics, to compare how things work in practice and in research. As a result, they came up with four criteria for good design research.

First, what they call Relevance: a good Research through Design project first explains how the world is today, and defines a clear direction, a new state of the world. In other words: as a designer, you need to have a vision. You need to know what you’re trying to bring into this world, or what possibilities you’re curious to learn more about.

Process means that your research methods need to make sense. You need to choose – and of course, execute – with care. (We will return to this.)

The next one, Invention: you need to go and find what is out there already, and tell us what you’re doing differently. If you’re doing Facebook, you should do know about MySpace, and tell us how you're different. If you’re doing Ethereum, you tell us about Bitcoin.

Finally, Extensibility: you could call this "impact." We should understand this better through examples…

Before we get to the examples: notice that some of these are properties of how you actually do the research. Process: you need to decide and execute from the beginning. Others could be properties of how you articulate your work in the end – how you write about it. A lot of people conflate these things. Your vision for the project could change between when you got started and when you write about it in your thesis or paper. Remember this, if you’re going to try it at home.

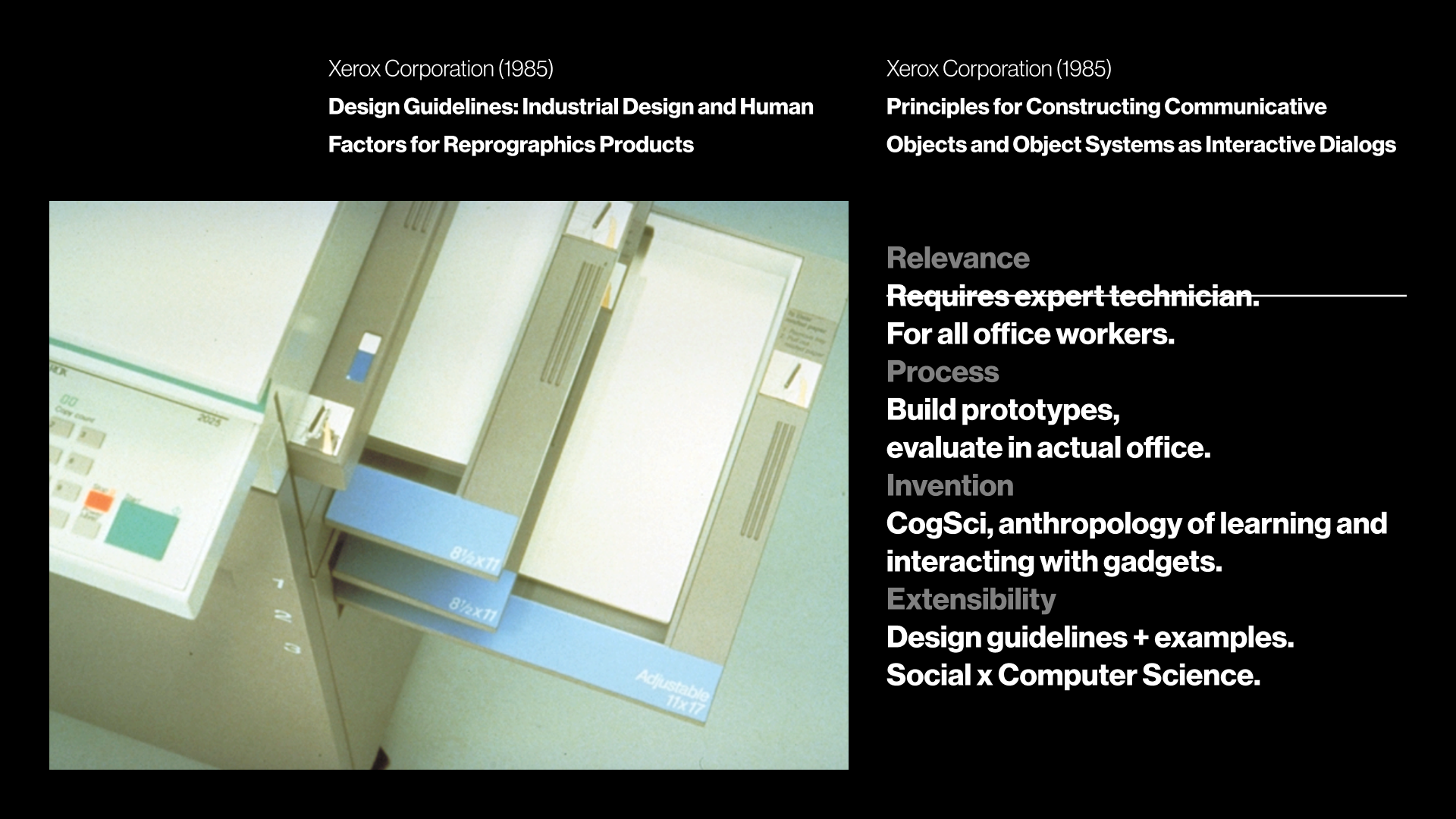

Here's an example from Zimmerman et al.: Xerox, in the 80s, was making photocopiers that were complicated – to the extent that you might have to employ someone to take care of the machine, if you bought one. You had to have a printer technician, which meant they could only sell to companies who could afford that. They wanted to figure out how to design machines that everyone could use, and expand their market to smaller businesses that couldn’t afford a technician.

They produced prototypes for these "user friendly" machines, and put them in actual offices where people were working. They employed anthropologists, psychologists, and other kinds of scientists to analyze the impact of doing this.

One thing that’s interesting to notice is that Invention means more than making new gadgets. In this case, they published a lot of research in cognitive science, psychology, anthropology…. And the impact – or Extensibility – was massive. This became a whole movement in computer science. It's basically the beginning of what we now call Human-Computer Interaction.

(Technically this is what we call the “second wave” of HCI, but that’s a whole other talk…)

It's also interesting that this was done in the 80s – before the “invention” of Research through Design. When they published results, it was in anthropology, sociology, and psychology, along with “handbooks” for designers and engineers. With this I'd like to repeat the point that Research through Design is more of a way of explaining or labeling what you’ve done, rather than a recipe for doing it. And this also suggests that, to do Research through Design, you might need a bit more than Research through Design itself! We’ll get back to this in a moment.

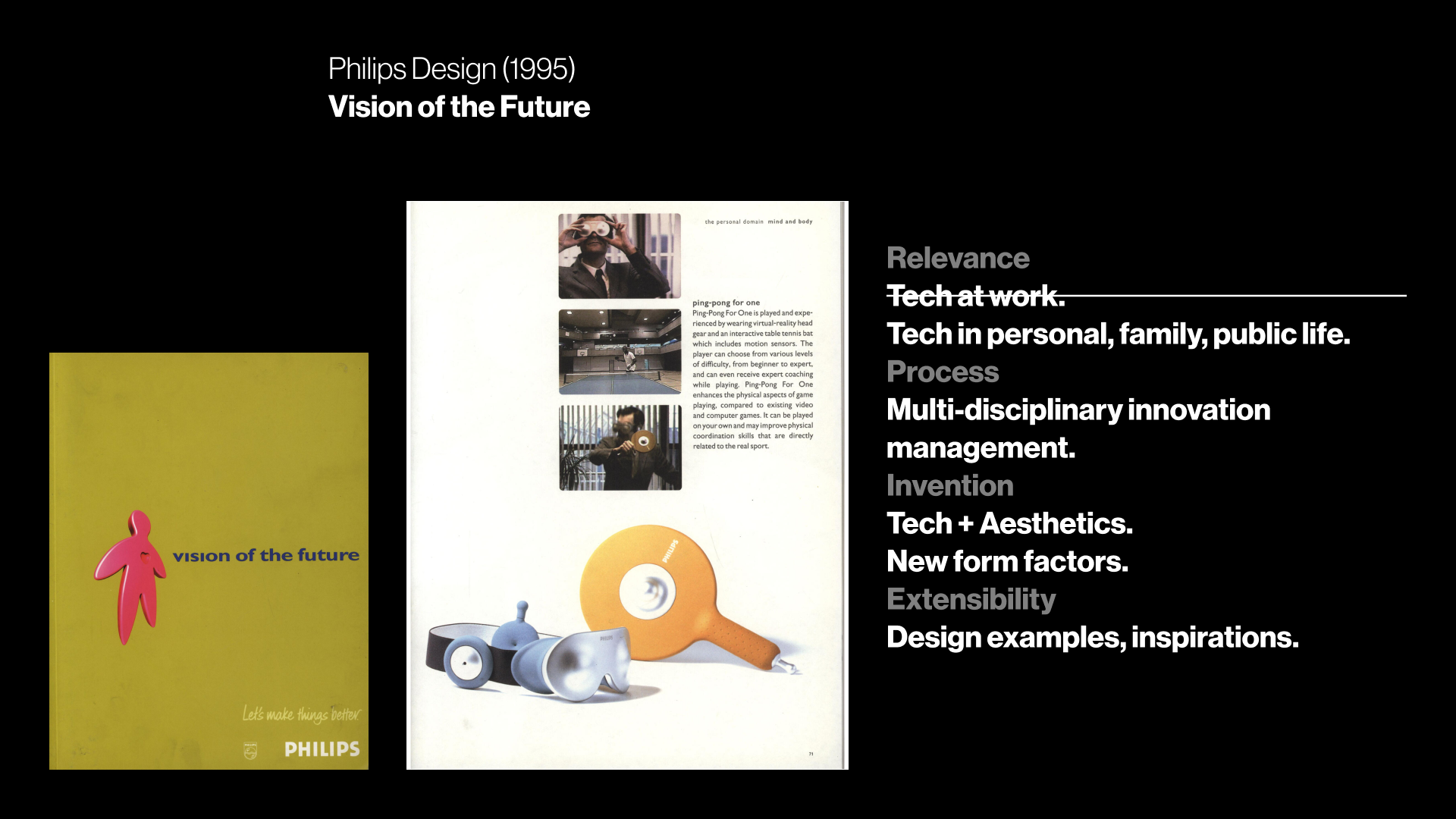

The second example in this paper is from Philips. In the 90s, they saw that computers are popular for business. But what about for fun? So they put together multi-disciplinary teams: artists, product designers, engineers... They invented… Rounded corners... What looks like the Oculus Go, and the Nintendo Wii... They laid out many form factors that we’re still aspiring to produce today.

They published this work as a book. The Extensibility of this is due to the fact that people – engineers, researchers – could take many of these concepts and develop them further.

You might notice that these two examples are not academic research – this is Xerox and Philips. You might ask yourself why they have invested in this. But before that, I want to talk about something else: research methods.

How To

I had said two things I'd like to remind you of. One was that you need to choose and execute your research methods carefully. The other was that, to learn how to do Research through Design, you might need to look outside of Research through Design. (It’s only 2,000 papers – that's not enough!)

But where are you going to look? How will you choose your research methods?

One of the best resources you can find today on Research through Design is the book called Design Research through Practice.* It's not a very challenging read – it's 10 chapters, and each took me less than half an hour go through – but it saves you a lot of time afterwards.

There are a lot of things being said in this book, but here’s the takeaway that I want to tell you about: If you’re going to do this kind of research, of course you want to do some kind of hands-on design, making software, graphics, UX impact journey canvas things… But, in addition to that, you also need some kind of scientific or academic discipline outside of design! You need to go deep into a "scientific" research discipline, learn that, and become that kind of researcher: a psychologist, or anthropologist, or a scholar of critical theory…

The point is that, in addition to design, you need to learn and execute a more "established" research method. The problem is that these are very dense subjects. When (I think) I understood what anthropology is, I was in the final year of my PhD, writing my thesis. Sociology, I still don’t know! It takes time, which you do not have, since you’re supposed to be doing design.

At the very least, you need someone to tell you where to look, and which discipline to study. This is what you find in this book: based on things that you already know as a designer – your concept, your technology, your research question, etc. – how can you then choose what academic discipline to bring into your design research? You have three choices – three broad “classes” of disciplines you can turn to:

- Lab is if you’re doing studies and experiments in a controlled environment, bringing people into your space. In this case you need to study psychology, cognitive science, the scientific method, hypothesis testing...

- Field is if you’re deploying your design out there, into the world: going to people’s homes or offices, going out on the street… For this you need social sciences. You need anthropology, sociology... This could involve politics, participatory design, public engagement…

- Showroom is where it gets artsy. In the previous examples, the Xerox stuff was mostly in the field, and some of it in the lab. The Philips stuff was more Showroom. That said, in actual academic research, this approach comes with a few more expectations, especially today: you need to bring in humanities scholarship, like critical theory.

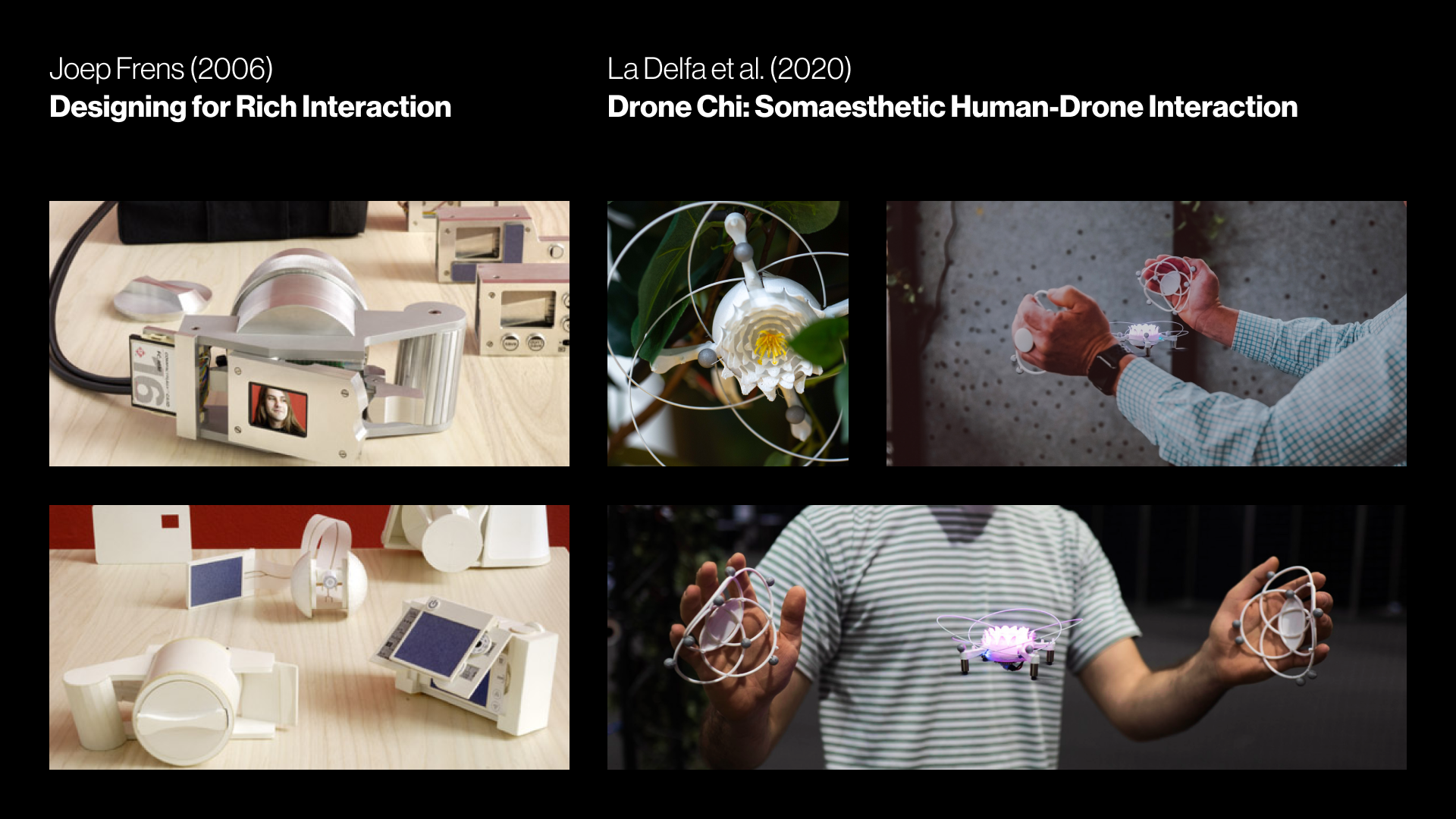

One example of Lab in the book is from 2006, when digital cameras were fashionable. This is pre-iPhone – if you wanted to take photos, you carried a camera. Joep Frens from Eindhoven University built models of digital cameras with physical controls, and brought people in to do user studies.

From our own research, I'd like to give the example of Drone Chi. This is a meditative movement exercise that you do together with a drone, similar to Tai Chi.

Credit for designing and engineering Drone Chi – as well as coordinating the whole research effort – belongs to my dear friend Joseph La Delfa.

With these examples, I want to illustrate why you would choose to do research in the Lab: this stuff doesn’t work anywhere else!

If you look carefully, you can see a cable coming out of one of the camera prototypes. Remember: this is pre-iPhone. It’s pre-Raspberry Pi. It’s roughly pre-Arduino. This whole thing is probably hooked up to a master race desktop PC in the lab…

The drone is flying inside a motion capture system that costs on the order of $50,000. The drone itself is $300 – not including the bespoke 3D-printed parts (priceless). When we took the drone to an exhibition outside the lab, we ended up spending 8 hours to unbox and assemble, plus another half-day for teardown. This goes on and on… The bottom line is: this thing is not flying outside the lab. (It barely flies in the lab – battery life: 4 minutes.)

If you find yourself in this situation, a good starting point for your research is the scientific method and experimental psychology literature.

That said, take these as guidelines and ideas to get started, rather than rules. Indeed, in our research with Drone Chi, we haven't actually used those methods! However, we had a really good supervisor and a genius PhD student who knew what they were doing, so the methods still add up to a rigorous “Process.”

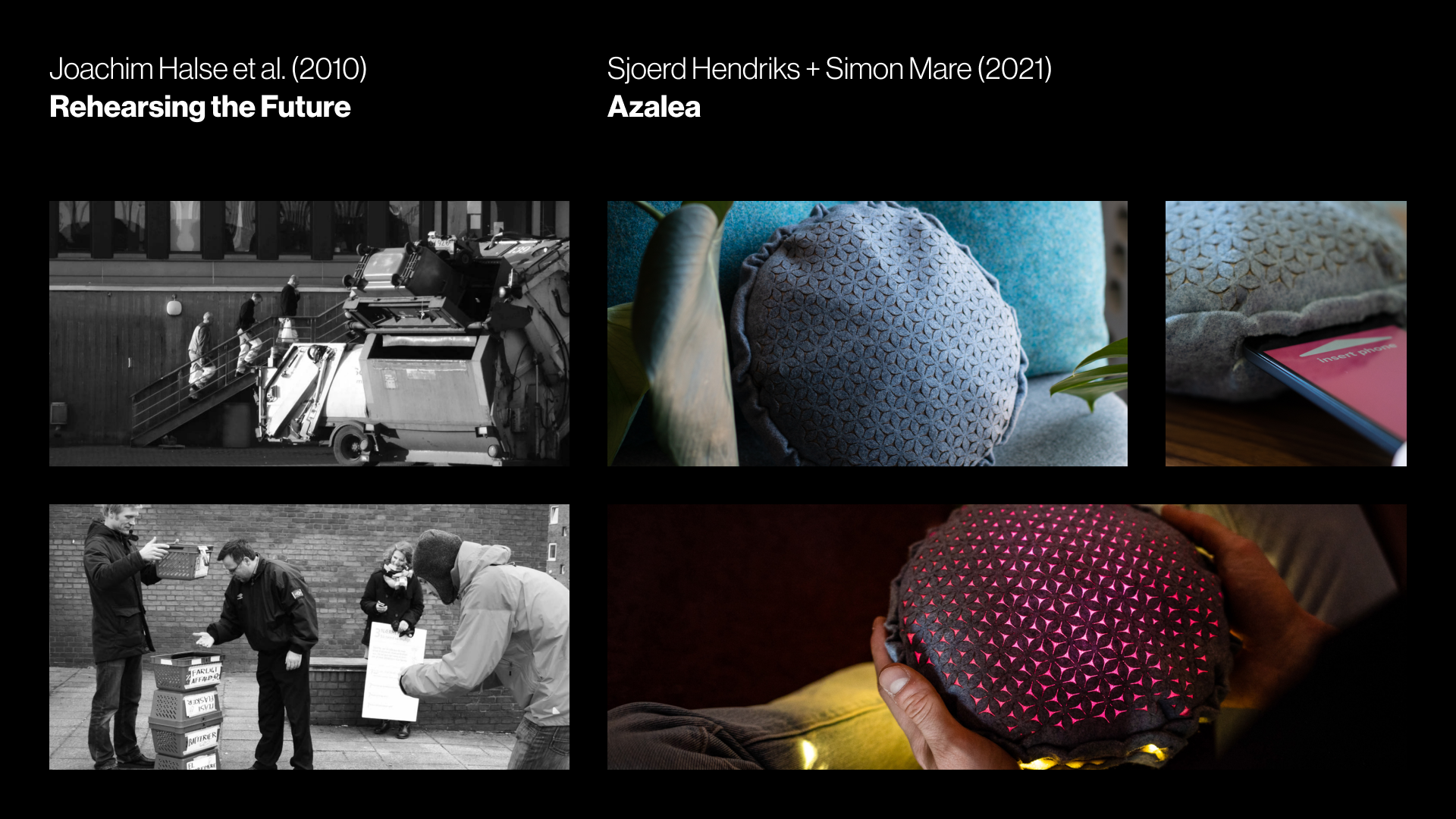

Regarding the Field, the example from the book has to do with community engagement, public spaces, urban architecture…. By definition, this happens outside the Lab.

Another example I like is a master’s thesis by our students: a design called Azalea. It looks like a cushion, and "swallows" your phone to activate. Once your phone is in, you can have a phone call on your headphones. Azalea will radiate light and add a soundscape to your conversation while you do that. Because of how it behaves with the light and everything, this design is supposed to influence how you behave, while you’re talking on the phone. It motivates you to turn off distractions – to actually turn off the lights in the room. It’s designed to be used at the home, and that’s where it makes sense. Thus, the studies with this design were done at people’s homes.

If you’re going to do this, the foundation that you need will be in social sciences, like anthropology and sociology.

The Showroom stuff, to be honest, is a bit more esoteric. It has to do with critical theory, artistic vision, and “aesthetic accountability.” This means that you need to make some kind of philosophical statement, as well as a well-crafted design.

Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby are the masters of this. They have written a few books (like Design Noir* and Speculative Everything*) about their projects and approach – speculative design and critical design.

My take-away is that these designs need to be enticing. They need to be visually interesting, to capture an audience, and to get them to think about serious topics. Take the blobby white design we see in the picture – I actually don’t know what that is... But it makes me really curious! What are they trying to say? It makes me engaged!

PEP is another example which I really like, again done by our students. The artifacts and the photography are meant to draw you in, to lure you – perhaps to a website, or a brochure, or other commentary – so you become engaged with certain issues. In our case, the project was actually about what teenagers in Sweden expect from the future, and how that affects their mental health.

Reason to Be

This conveniently brings me to: why? What purpose can we serve with Research through Design?

What I can identify is two kinds of research questions that make sense to address with Research through Design.

The first is about design itself. Specifically it’s about informing people who want to design effectively, with particular materials or technologies that we don’t really know how to handle yet. This doesn’t have to be “technical.” It could also be about the process or management of design. It could be about how to engage with different stakeholders, in situations that we don’t yet know how to deal with.

The second kind of question is about people. How do people think and behave? What is it like to be that person, in that situation? Or, at a collective level: how can we articulate what we know about organizations and societies, in order to navigate better?

Research through Design enables you to deal with these questions, by way of doing design.

If you want to make a printer that everyone can use… Is it enough to just design a good printer, and drop it in? Or, when you do that, does it affect the habits and social relations of people at the office? You can find out by doing Research through Design.

The best Research through Design projects actually do both of these things. Will Odom, based in Canada, is one of my favorite design researchers. The Slow Game is an example from his work where they deal with design and manufacturing, as well as the user experience, in the course of the same project. It’s actually a Snake game – like we had on the old Nokia phones. It's controlled by rotating the cube. The catch is that the snake moves only one square every 24 hours! They have published papers where they talk about what it's like to live with this design, as well as how they produced it with special wood and fabrication processes.

Will is really good writer, and so are almost all of his colleagues and students. If you want to get into this field, I would very much recommend reading his work.

For Fun and Profit

The three resources I commented on – Frayling, Zimmerman, and Koskinen – are canonical. These are among the foundational texts of Research through Design. Almost all of the literature on Research through Design is connected to these via citations, and you can "crawl" them (for example, on Google Scholar) to find more interesting work.

Before we conclude, I want to point out two examples of “commercial” Research through Design. These are not necessarily labeled as Research through Design by the people who do them, but they illustrate the possibilities.

SPACE10 is lab in Copenhagen which is supported by Ikea. They publish reports, videos, and concepts which are very compelling, in lieu of academic papers. In fact, I believe that they are setting the perfect example for how to express this kind of research – well-designed, self-published reports, rather than academic literature. This is what we should have more of. I really look up to their example.

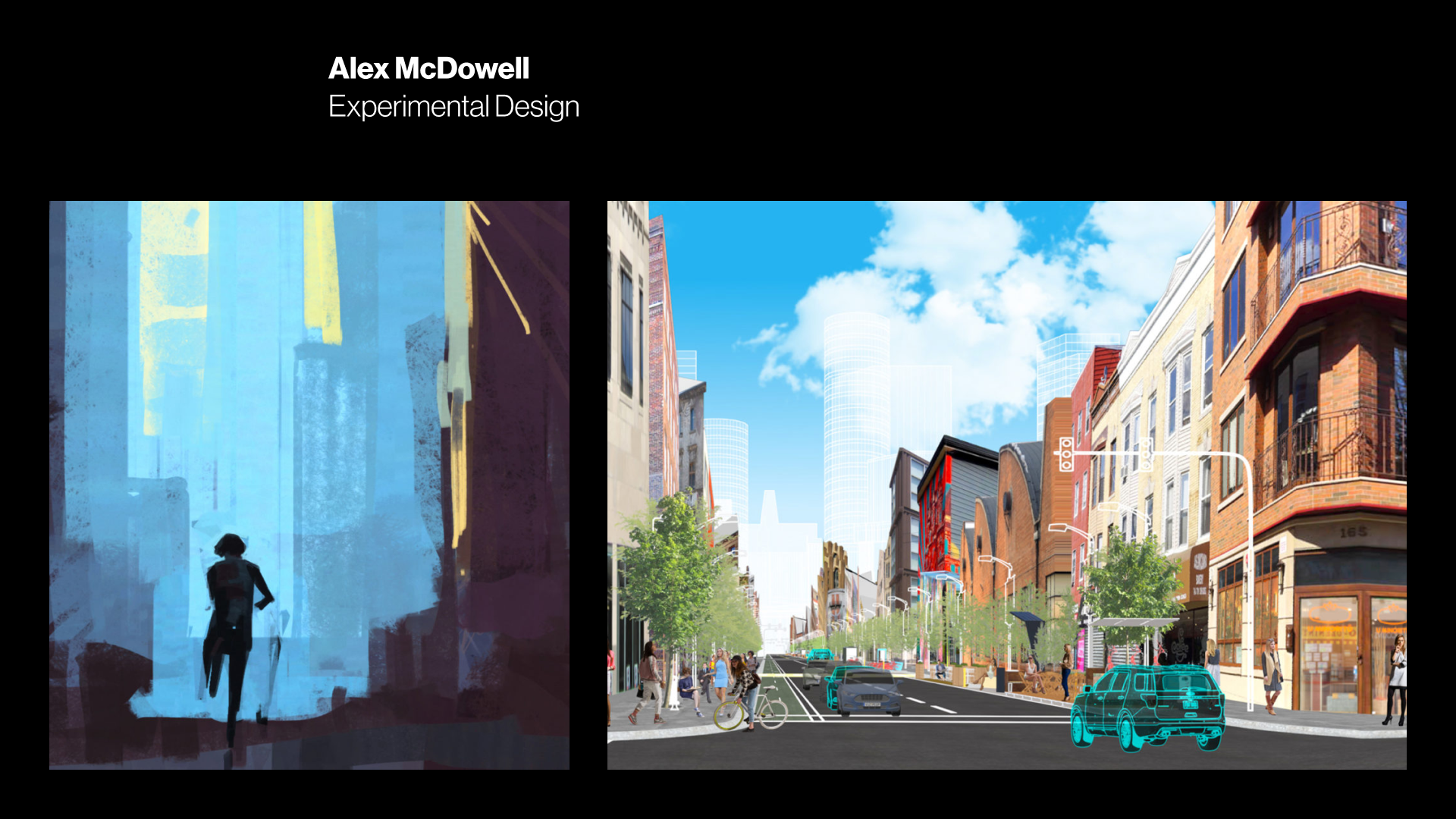

Finally: the example of Alex McDowell and his company Experimental Design. McDowell is actually a set designer and director, known for his worldbuilding and environment design for science fiction. He also works with companies like Nike and Ford (shown on the slide), on projects we can consider Research through Design or design fiction. Unfortunately, he doesn’t publish a lot of detail on his projects – his corporate clients care about confidentiality. But the visions and directions on his portfolio are compelling.

Conclusion

To conclude, here are my points:

- Research through Design was born as a way to adapt design to academia. It allowed us to have design professors and departments; to have design as an academic field that commands respect and prestige, which comes by way of writing.

- We can use Research through Design to understand people and the world. We can also use it to figure out how to deal with materials, technologies, and situations that are new. It helps us deal with the complex reality of today, as well as the future.

- Doing Research through Design actually requires expertise that comes from outside of design: anthropology, philosophy, engineering… It's interdisciplinary.

- Research through Design is useful for much more than writing academic papers – we have seen examples from Xerox, Philips, Ikea… Because it tells us about our customers, and materials, and management… It's very good for business.

Not only does Research through Design tell us all those things, but it also allows us to be creative, in the truest sense of the word. That’s also good for business – in certain places. I hope that, where you work, it’s one of those places.

Special thanks to Mathias Funk (@matsfunk) for his most valuable comments as I edited the transcript.

Links + Resources

Books

- Change by Design* by Tim Brown

- Design Noir* by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby

- Design Research through Practice* by Ilpo Koskinen, John Zimmerman, Thomas Binder, Johan Redström, and Stephan Wensween

- Speculative Everything* by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby

- Sprint* by Jake Knapp

- The Lean Startup* by Eric Ries

Papers

- Bowers (2012). The Logic of Annotated Portfolios: Communicating the Value of ‘Research through Design’. In Proc. DIS. [ACM Digital Library]

- Desmet, Overbeeke, & Tax (2001). Designing Products with Added Emotional Value: Development and Appllcation of an Approach for Research through Design. The Design Journal, 4(1). [Taylor & Francis Online]

- Frayling (1993). Research in Art and Design. Royal College of Art Research Papers 1(1). [PDF from rca.ac.uk]

- Gaver (2012). What should we expect from research through design? In Proc. CHI. [ACM Digital Library

- Hauser, Oogjes, Wakkary, & Verbeek (2018). An Annotated Portfolio on Doing Postphenomenology through Research Products. In Proc. DIS. [ACM Digital Library]

- Zimmerman, Forlizzi, & Evenson (2007). Research through Design as a Method for Interaction Design Research in HCI. In Proc. CHI. [ACM Digital Library]

- Zimmerman, Stolterman, & Forlizzi (2010). An Analysis and Critique of Research through Design: towards a Formalization of a Research Approach. In Proc. DIS. [ACM Digital Library]

Projects

Misc.

- Alex McDowell (Wikipedia) and Experimental Design

- Design Issues Journal

- Design Studies: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Design Research

- The Three Faces of Design Research on Design Disciplin

- The Profession of Human-Computer Interaction on Design Disciplin

- The Story of Design Thinking on Design Disciplin

- Phase-gate process (Wikipedia)

- SPACE10

* Affiliate links – at no extra cost to you, we earn a commission if you purchase from these links.

Comments? Join the discussion on Twitter:

Presenting an off-schedule article:

— Design Disciplin (@designdisciplin) December 8, 2021

Crash Course in Research through Design

Research through Design is a way to materialize knowledge and insights based on hands-on design work.https://t.co/wxR85Rcs2I